In the early summer of that year we traveled to the pleasant peninsula to look about and to see the lakes and the dunes. In the places of rest, old and new establishments, we found hospitality and new friends, and the waters we sought were vast and blue and the hills that carried us to the shores were undulating and sandy and rocky in places.

It was my first trip to Michigan.

The state eluded me until now. I grew up moving all over the country, but missed it somehow. My doctoral work centered on Ernest Hemingway’s life and literature intertwining with my own; Hemingway brought me here to Michigan. I embraced the state with curiosity and honesty and joy. (It helped that my husband is a Wolverine of the Ann Arbor branch and found himself revisiting some former stamping grounds.)

Here we were, on a bright Friday morning in Petoskey, when others made their way to work at a more hurried pace and we gingerly drove the streets until coming upon the park.

“There he is,” my husband said, pointing.

“No, that’s not him.” He’s too slight, I thought.

I parked the rental vehicle at the metered slot. I glanced to ensure no traffic impeded me, opened my door, and walked to the statue just ahead, yards from the famed Annex he is said to have enjoyed a century ago.

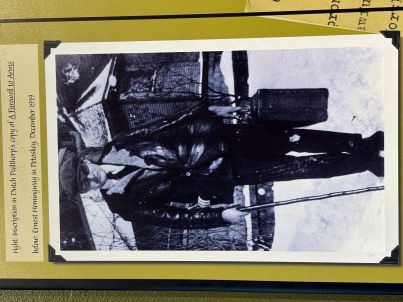

Moving closer, peering into the face, the emotion caught in my throat — this was no Papa Hemingway, as I had expected (and come to expect with other memorials to the man). I had not researched the full story behind this particular piece, just put it on a long list of Hemingway-musts on our short visit up north. Here he was: not the older, wizened, bearded man most think of when they think of him; no, this is the young man I visualize, the one whose image I show my students to hook them. “Who is that?” they ask upon seeing the square jaw and dark eyes.

This was Ernie. Young, still recovering, a noticeable tilt in his stance, but a young man on a mission to prove himself. I felt the piercing of the injury, and the cane, and the small smile, and I smiled, too. It was this feeling of connection that led me through my research, my reflection on my own life-altering trauma. How many of us can relate to the young hero embarking on the journey, the one already scarred — but young, still — and with so much potential? I’d been scarred, too, at that young age, but my wounds were not visible. There was no cane.

I saw then the pocket of his jacket and the ever-present notebook. I smiled again: Ernie waiting for his train with pencil and notebook, and the words and adventures and years ahead of him….

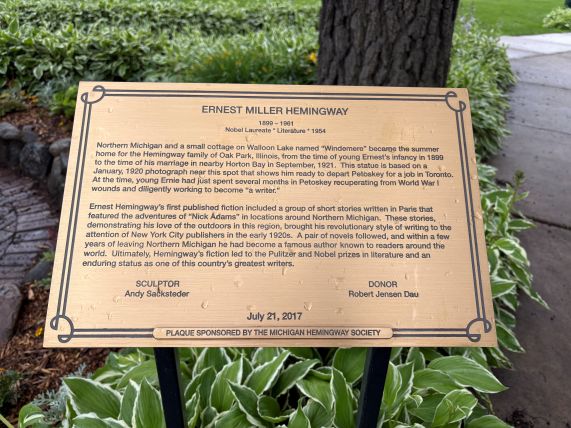

Thank you to the Michigan Hemingway Society, sculptor Andy Sacksteder, and donor Robert Jensen Dau for making the memorial to young Ernest Hemingway possible — and for making the moment for me and others like me possible.

Tracie Nicolai is an award-winning teacher and scholar, as well as a trauma researcher and victims' advocate. Her Hemingway-focused research project, So Much Courage: Hemingway, War, and Rape, examines Hemingway's depictions of trauma in his fiction, expanding on the war-and-rape PTSD described and juxtaposing it with her own experiences of trauma at 18, the age at which Hemingway was injured in World War I. She lives in Florida.