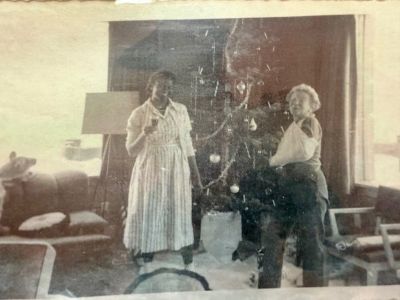

Images in a photo album in the Hemingway House in Ketchum, Idaho, bring the home to life, showing the Hemingways enjoying the company of local friends. One photo captures the lively atmosphere around the dining table, good times accompanied by wine served from an elaborate hanging decanter. A serious-looking Ernest tends to the candlelit table, and Mary looks chipper even with her arm in a sling protecting her shattered elbow. Those invited are groomed and bejeweled, glossy-haired women accompanying men spiffed up in bolo tie. Raised glasses, cigarettes in hands. Seated at the table, a young Black woman appears to observe quietly, hoisting neither glass nor cigarette.

A letter from Mary Hemingway tells more about the woman, Lola Richards, with Mary expressing concerns about how her Cuban helper would be received in their small community, providing a snapshot about race and foreign-ness at that moment in time.1 To join the Hemingways in Ketchum in late 1959, Lola would travel far from her Caribbean home to an isolated, homogenous town with fewer than 1,000 residents.

This blog post was inspired by conversations with Mary Tyson, Director of Regional History at The Community Library in Ketchum and one of the hosts of our stay at the writers-in-residence apartment below the main house.2 Today the private home-museum displays authentic artwork, books, records, clothes, and other personal items, such as Ernest’s hunting boots and Mary’s writing desk. The provenance of many of the artifacts is clear, while others spark curiosity. Mary Tyson said she would like to know more about Lola, a key member of the Finca Vigia staff who accompanied Mary Hemingway to Idaho to help set up the home.

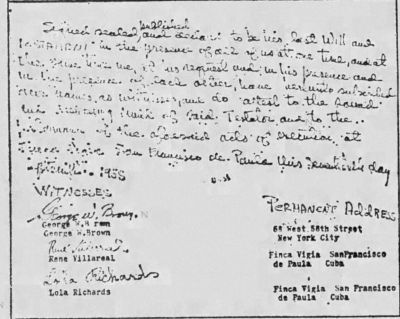

Some of Lola’s life story appears in Mary Hemingway’s autobiography How It Was.3 Lola kept her job even after mistakenly burning as trash a “Welcome to San Isidro” drawing created by the artist Salvador Dalí and presented to the Hemingways. Mary had wrapped the artwork in tissue paper and packed it with favorite dresses as part of the 87 pieces of luggage she and Ernest sent home to Cuba after 13 months away. Mary discovered her dresses hanging in the closet and wept over the lost treasure (398-99). Lola was also one of the witnesses to Ernest’s last will and testament (426). When Fidel Castro took power, Lola went to hear him speak, but she tired of the crowds and came home early (478). Mary found the Finca staff shrugged off politics, Lola “too relaxed and comfortable to disturb herself with vague issues,” and her sister Sonia the cook unconcerned with affairs beyond her own, even as their world was about to change (451).

Mary Hemingway shares more about Lola in an October 1959 letter to Dr. and Mrs. George Saviers in Ketchum. She writes that Lola has been with the Hemingways for years at the Finca, first as a housemaid and in recent years as a cook. Both nice and intelligent, Lola speaks English well, has a passport, and likes the idea of traveling to the United States. Naturally Mary believes Lola will be a big help getting established in the Ketchum house and keeping it going.

But she has questions for the Saviers: do they think either the people of Ketchum, or Lola herself, would feel “uncomfortable or miserable” if Lola joined Mary at their home in Idaho? Mary says Lola is young, in her mid-to-late 20’s, and Mary will not countenance her feeling hurt or insulted. Furthermore, if the Ketchum community is prejudiced against Black people, Mary does not wish to make an issue of it, embarrassing everyone. But her thought is that if nicer people lead the way on “new questions” such as this one, others may be apt to show acceptance.

Acknowledging her inquiry may seem “silly and/or unnecessary,” Mary explained that the Finca team is composed of people with a rainbow of skin tones and eye colors, and they work in harmony together. When problems arise, they address them on the basis of “character, endeavor, efficiency, etc.” without regard to appearances. Mary would like the Saviers to share their opinions on this matter, without mentioning it to anyone.

Considering Lola in this context gives a name and a face to a trusted staff member who experienced life with the Hemingways. Mary’s tentative, awkward inquiry showed consideration for both her new community and Lola, and indicated she valued character more than appearances. Would Mary have posed the same questions today? The Saviers’ response is not known, but must have been reassuring, as the photos show Lola was welcomed at the table and in the Christmas celebrations.

1 Hemingway, Mary, to Dr. and Mrs. George Saviers. 29 October 1959, Mary Hemingway Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

2 Meeting with Mary Tyson at Hemingway House, November 2024.

3 Hemingway, Mary Welsh. How It Was. Knopf, 1951.

Greer Rising and Eileen Martin are working on a book based on letters from Buck and Pete Lanham to Greer’s family that will explore the friendship between Lanham and Hemingway, a topic they explored on One True Podcast in September 2025. They have previously blogged on Hemingway's "Devil Box," "Hemingway's Imaginary Dinner Guest," and "How Do You Like It Now, Gentlemen?" (on Lillian Ross's New Yorker profile of Hemingway).