Has what could very well be Hemingway's first contribution to a professionally published newspaper—and it's not the Kansas City Star—gone unnoticed all this time?

While rummaging through an archive1 of Ernest's hometown newspaper Oak Leaves, of

Previously known as the Oak Park Vindicator, from 1881 to 1901, Oak Leaves was established in 1902 as a weekly publication serving the residents of the newly incorporated

In January 1916, at the start of the second semester of his junior year in high school, Hemingway began writing for The Trapeze, which operated under a revolving editorship by the students.4 As he experimented to find his own sense of style, he often mimicked the acclaimed Chicago Tribune columnist Ring Lardner, whom he greatly admired. Copying Lardner's pseudo-illiterate style, Hemingway took on the persona of "Ring Lardner Junior"5 as narrator for humorous pieces that were written in the form of letters,6 addressed to whoever was editing the newspaper that week. By the time Hemingway graduated, he had thirty-nine publishing credits in The Trapeze, five of which capitalized on Lardner's name.

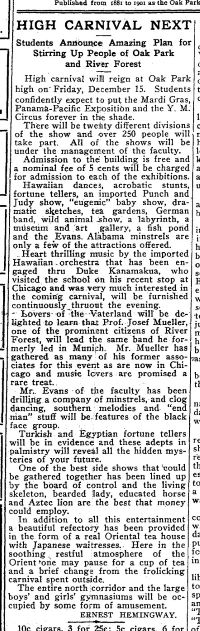

In "High Carnival Next," though, Ernest's style was far from the laidback, mellifluous written-word wanderings of Lardner. Instead, what readers encountered could easily be thought of as a high school student utterly gushing—laying it on rather thick in describing the grandeur of the carnival. Foretelling a night of wild animals, fortunetellers, acrobatics, and a whole host of frivolities ranging from a bearded lady to an educated horse, Ernest promised it would be a night that would "put the Mardi Gras, Panama-Pacific Exposition and the Y.M. Circus forever in the shade."

It's his mention of the "Y.M. Circus" (the Y.M.C.A Circus) that lends a small clue toward understanding Hemingway's seemingly over-enthusiastic writing. Hemingway loved the circus, which would remain a passion throughout his life.7 It's quite possible that attending

Albeit with a bit of dramatic flair, young Ernest had described the whole affair of the carnival quite accurately.9 More importantly, though, this article appears to be the only contribution Hemingway ever made to the newspaper, although after his wounding, in World War I, plenty was printed about him (including material provided by friends and acquaintances of friends, and even letters home from Ernest that had been forwarded to the newspaper by someone within his own family).

Unable to recall having encountered mentions of "High Carnival Next," yet wanting to know more, particularly what circumstances had led Hemingway to receive this single publishing credit in Oak Leaves one year before his first Kansas City Star article, I began scouring indexes and text from my library of over 300 Hemingway-related volumes to see what I could find.

The answer is nothing.

From Audre Hanneman's Comprehensive bibliographies, to Carlos Baker and Michael Reynolds and every other biographer in between, to the works of Matthew J. Bruccoli and journals such as Hemingway Notes and The Fitzgerald/Hemingway Annual and The Hemingway Review and everything else possibly relevant right up to Brewster Chamberlin's Hemingway Log, it appears no one had written about this. Nor did Hemingway write about it (at least as far as we know from surviving letters of the time). This is something very old, yet totally new.

Over sixty years after his death, previously uncataloged Hemingway items continue to turn up to this day. The Hemingway Letters Project alone has prompted folks to search old trunks and drawers, looking for the familiar slanted penmanship or broken-machine-gun-spaced typewriter print from the prolific letter writer. Some letters have been found.

While nothing could ever match the thrill of discovering Hemingway's very first surviving bit of adolescent prose among a cache of goodies tucked away in

To share in that excitement, I offer this clipping10 of what is likely Ernest Hemingway's very first professional credit, "High Carnival Next," published in the first semester of his senior year of high school:

1Made digitally available by newspaperarchive.com

2Because of this technicality, over the years the town of

3Pashley was one of the former classmates contacted by the Chicago Daily Tribune for a statement after Ernest's death. Pashley, who was a retired business executive, recorded Hemingway as being an "exceptionally good writer" during his school years. ("Genius Hinted by Hemingway as School Boy."

4Hemingway would edit the final issue of 1917. (Oak Leaves, 19 May 1917, p. 9)

5The real Ring Lardner Jr. was one of the "Hollywood Ten"—the ten screenwriters and directors who were convicted and imprisoned for contempt of Congress after refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, and were each subsequently blacklisted.

6Ring Lardner's book You Know Me, Al (1916) was about a minor-league baseball player, presented in the form of letters written to a friend.

7Hemingway even contributed an essay to the Ringling Bros and Barnum & Bailey Circus Magazine & Program, in 1953, titled "The Circus."

8

9A total of three articles about the carnival were published in Oak Leaves; Hemingway's was the first one. Earle Pashley wrote the other two articles, the first of which bore the same title as Hemingway's piece: "High Carnival Next" (9 Dec 1916, p. 49) and "The High Carnival" about the aftermath (23 Dec 1916, p. 6.)

10Hemingway, Ernest. "High Carnival Next." Oak Leaves, 2 Dec 1916, p. 14. Accessed via Open Athens (https://access-newspaperarchive-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/us/illinois/oak-park/oak-park-oak-leaves/1916/12-02/page-14/)

John Hargrove is a Michigan-based writer and Hemingway researcher; he is also thefounder of "Ernest Hemingway: The True Gen," an online community of Hemingway researchers and aficionados hosted on social media. He is the author or co-author of previous blog posts on "Hemingway's Pamplona Legacy," "The Saga of the Socket Photo," and "Adventures in Buffalo, Wyoming."