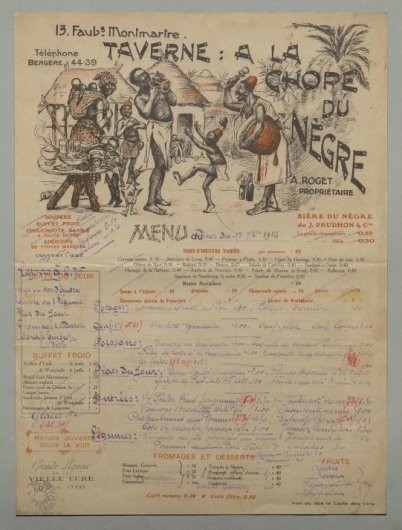

The second menu of Chope du Nègre, dated 17 February 1916, shows that the tavern used the same template for several years (Figure 2). This earlier menu highlights in red some details of the village scene, making the characters’ lips thicker and their grins larger, which worsens the offensive representation of Black Africans. Both menus identify the tavern’s owner as A. Roget, about whom I have been unable to find more information.

FRCGMSUP751045102P02/BHPEP021961/v0002.simple.

selectedTab=record)

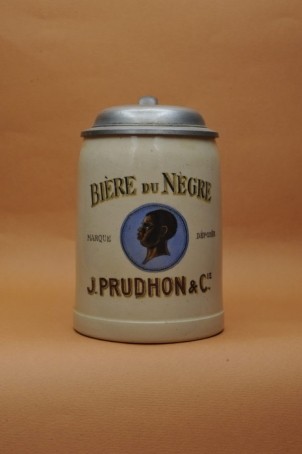

The menus also indicate that the bar sold Bière du Nègre made by the beer establishment J. Prudhon & Cie. Figure 3 contains an image of a stoneware mug with a metal lid made by J. Prudhon, revealing what its beer products might have looked like. Although I have not yet verified the production date, the stein is stamped with “Marque Déposée,” meaning “Registered Trademark.” Whatever the date, the Black man on this tankard resembles the caricatures of the Black Africans on the menu, with his thick red lips and dark features.

As my research discloses, the words “nègre” or “négresse” were often accompanied by offensive caricatures of Black Africans. This was not unusual in 1920s Paris despite its policy of racial tolerance. Scholars have pointed out that the popular craze for African and African American art, music, and dance did not reject stereotypes. Sometimes these stereotypes were given positive value, but the stereotype was not dismantled. Other times Black people and culture were celebrated so long as they reproduced established stereotypes. For instance, Josephine Baker’s performance in La Revue Nègre (1925)—especially her danse sauvage with partner Joe Alex—projected animalistic representations of Africans and African Americans. Some thought her performance was denigrating, whereas others praised it for transfusing new blood and energy into a France sorely in need of renewal (Dalton and Gates 916). Each side was reading the animalistic and erotic stereotypes differently but still spreading them. Black Africans and Black Americans, like the drummer at Zelli’s, might have experienced some tolerance and admiration in Paris, but the signs of their imagined inferiority were present everywhere, even in a popular tavern in the Opéra district.

Debra A. Moddelmog is dean of liberal arts emerita and professor of English emerita at the University of Nevada, Reno. She co-edited Ernest Hemingway in Context with Suzanne del Gizzo and is the author of Reading Desire: In Pursuit of Ernest Hemingway. Her edition of The Sun Also Rises was recently published by Broadview Press. Feedback can be sent to dmoddelmog@unr.edu